What if transportation abundance policy focused on access, not just mobility?

By Juan Matute

In a position paper for the Abundance Policy Research Consortium, I argue that transportation policy should prioritize accessibility, especially in cases where pursuing accessibility as a goal appears to conflict with pursuing mobility.

I see several problems with current transportation policy approaches that I wanted to address in writing An Abundance Agenda for Transportation. The first is affordability of mobility and access, which is deeply interconnected with housing costs. The second is the localized health, safety, and environmental impacts from transportation, which are often overlooked in transportation policy. The third involves upstream, or global, environmental impacts, including climate change. And the fourth is that many approaches address the symptoms of traffic congestion rather than the causes, often in ways that suppress economic activity

In my paper, I argue that an abundance policy for transportation requires rethinking how we invest in and manage the system to make it easier for everyone to get to what they need.

From Mobility to Accessibility

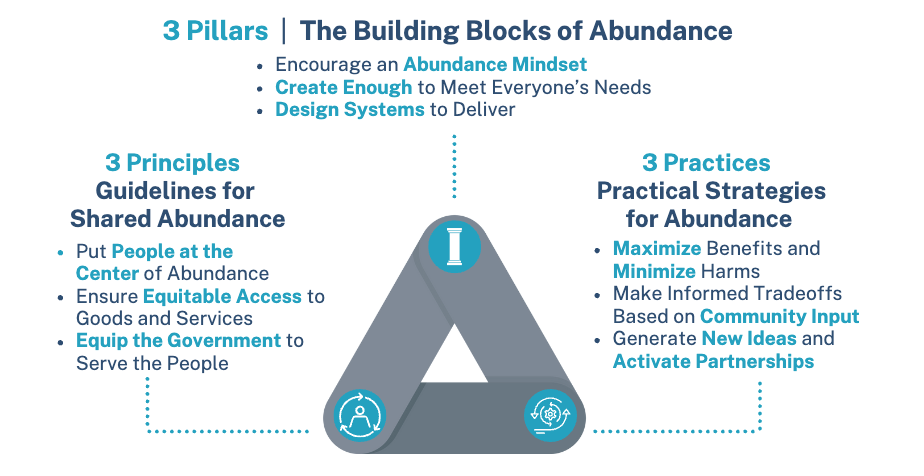

My charge from the Abundance Policy Research Consortium was to develop a policy framework that aligned with their pillars, principles, and practices (seen above). I thought that an accessibility mindset, which considers the outcomes that the transportation system facilitates, would fit this framework much better than a mobility mindset, which emphasizes efficiency of intermediate outputs rather than outcomes.

I argue that the status quo is anchored in combination of a mobility mindset, a permeating tendency to address symptoms of problems rather than root causes, and focusing on short-term or immediate problems over long-term or cumulative problems, like housing affordability, impacts of air quality and transportation system safety on children’s health, economic growth of communities and regions, and climate change.

I also identified two core scarcities and four root causes for these scarcities. People use money, time, and energy for mobility, all of which are scarce due to varying factors. And access is a function of a person’s needs, time, and the distance they will travel. I argue that four root causes have combined to entrench a policy and governance approach that fails to manage these scarcities:

- Entrenched investment in the status quo.

- Poor management of transportation infrastructure.

- An unequal distribution of jobs and essentials throughout California.

- The slow process of changing policy and infrastructure.

Framed in this way, a transportation abundance agenda foregrounds several long-established principles: accessibility as a social indicator, an approach to parking and traffic policy rooted in resource economics, and a comprehensive approach to public transit that spans from travel behavior to benefit-cost assessments. In each of these areas, UCLA ITS has established research programs and a history of impactful scholarship.

Access to Opportunities

In 1973, the late professor Martin Wachs published Physical Accessibility as a Social Indicator, establishing a framework for evaluating transportation systems based not just on mobility alone, but on people’s ability to achieve the intended outcomes from mobility. Whereas most transportation performance metrics measure the movement of vehicles, and sometimes people and goods, accessibility measures seek to understand outcomes – how mobility helps people live their lives. I see the concept of accessibility as central to an abundance which prioritizes outcomes(the ends of mobility) over process (the means of mobility).

Today, Professor Evelyn Blumenberg leads a joint Lewis Center-ITS Access to Opportunities Initiative. Her work examines transportation and economic outcomes for low-wage workers. Her research into how women, low-income households, and immigrant households travel has shaped the understanding of these issues and shown that access to cars improves the lives of low-income people, a finding inconvenient to some policies that seek to reduce driving by restricting car access.

Parking

Abundance policy should identify a scarcity in what people need and address its root causes. In the United States, the goal of most transportation policy is to avoid scarcity by oversupplying infrastructure, treating scarcity as an indication of insufficient infrastructure rather than a misallocation or mismanagement of limited infrastructure. The policy approach to mandate a given quantity of parking supply through parking requirements means that the government primarily manages the parking system only when approving new buildings.

Government mandates to supply parking lead to overspending on parking infrastructure and spreading out destinations in order to supply more space for parked vehicles than is typically required.

The UCLA Center for Parking Policy brings academic research to parking policy reforms that manage parking as a scarce resource while reducing negative impacts on people, places, and the planet. The center continues the work of the late Professor Donald Shoup, a land use economist whose scholarship fundamentally reshaped how urban planners view parking policy.

Traffic, Road Space and Congestion Pricing

Roadway space is fixed in the short run, but demand varies by time and location. And yet transportation policy in the United States prioritizes using funding to expand roadways rather than actively manage existing scarcities.

Because roads are expensive to provide and maintain, it is far more cost-effective to manage existing roadway utilization than to expand capacity through lengthy environmental review, obtaining funding, and reconstruction. Pricing — essentially instantaneous rent to manage roadway space rather than letting competition for the same roadway space create traffic congestion — improves the function and utilization of roadway space and can be adjusted quickly to adapt to changes in conditions.

UCLA ITS research on congestion pricing shows that these policies can be designed to be more equitable than the status quo and, counterintuitively, enable more people to travel on a roadway during rush hour. Professor Michael Manville, who leads the institute’s traffic research program, communicates the real-world implications of congestion pricing policy better than anyone else I know.

Public Transit

I suggest prioritizing public transit in congested areas, because mass transit provides the most geometrically efficient form of mobility for urban agglomerations. These areas tend to be places where land is expensive and that attract high-technology fields. Public transit also serves walkable places, which tend to be good for physical and mental health.

Professor Brian Taylor is best known for his research on the geography and management of transportation, including public transit. He has helped California with research on declining transit ridership, public sector responses to new transportation technologies, and the economics of transportation. I worked for Brian for almost 15 years, including on research to support effective transit services that support the state’s economic, social, and environmental policy goals.

From 2023-2025, I served as an academic appointee to the state’s Transit Transformation Task Force, which recently submitted a final report to the Legislature.

My colleague Jacob Wasserman now manages the institute’s public transit research program and has developed his own portfolio of work on the intersection of transportation and other social issues.

“An” — not “The” — Abundance Agenda

Many individuals and groups are vying to define an “abundance” agenda, and there’s a wide range of thought on what “abundance” means. My view is that an abundance agenda must first define what is scarce that people need more of (e.g., housing at lower price points in high-cost areas, clean energy).

I think the fundamental scarcity is access, rather than parking, road space, or fast trains. Gregory Shill and Jonathan Levine’s “Transportation for the Abundant Society”, published just as I was finishing my position paper, seems to share this view. By contrast, some other viewpoints that begin with tools — such as deregulation — rather than goals rooted in addressing specific scarcities tend to adapt poorly to transportation.

With UCLA’s scholarship already serving as a cornerstone for many abundance discussions, I look forward to continuing the dialogue around transportation abundance.

Featured Image Credit: Possibility Lab/UC Berkeley

Recent Posts

UCLA student wins fourth consecutive national transportation prize

Nick Giorgio MURP ‘25 received the Neville Parker Award for his capstone project on intersection design and safety in Los Angeles.

Freeways and floodwaters, UCLA researchers model climate risks of highway expansion

A site visit to Shiloh, Alabama, revealed how a highway expansion created new flooding patterns and grounded climate-risk modeling in community experiences.

Featured Content